Paris, France: Rémy Cointreau

Rémy Martin XO Dégustation – Opulence Revealed

Élisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun: Portraits of Marie-Antoinette and Courtly Life

Élisabeth Louise Vigée le Brun still remains a relatively unknown female artist belonging to the Age of Enlightenment despite having achieved many notable successes. Born in 1755 during the reign of Louis XV, Vigée le Brun was raised in a family of artists who introduced her to the world of painting and fine art. She is perhaps most renowned for her portraits of Marie-Antoinette. However, she was never fully celebrated in France until the 21st century when the Grand Palais devoted an entire exhibition to the artist and her work.

Vigée Le Brun’s idealized representations of the Queen offer an innocent, serene, and spiritual interpretation of courtly life while highlighting the essence of royalty. Marie-Antoinette en grand habit de cour (1778) was the artist’s first official portrait which shows the Queen en grand panier. She is dressed in a voluminous, luxurious, white satin gown with exquisite golden tassels and trimming as her gaze is averted to the right. Her intricate lace bodice with princess seams and three-quarter length sleeves is carefully adorned with white, satin bows. This whiteness mirrors the paleness of her translucent, white flesh. A sophisticated feather hat sits atop Marie-Antoinette’s elegant coiffure. The Queen’s stance is both intimidating and gracious as she poses in the corner of a stately room holding one pink rose. Her crown rests inconspicuously upon a purple cushion embroidered with golden fleur-de-lis. It is situated next to a vase of pale pink, purple, and white flowers.

During this time, 18th century women began to opt for the robe chemise in mousseline cotton which did not require an obtrusive panier. These simplified garments were designed from one piece of fabric. They were preferred for their comfort and ease of movement. Vigée Le Brun’s portrait of Marie-Antoinette, La reine vêtue d’une robe chemise, was shown at the 1783 Salon, an exhibition space for the Royal Academy. The Queen appears in a white, cotton “peasant dress” with a transparent, golden sash tied around her waist. Her relaxed curls are topped by a simple, straw-feathered hat with blue satin ribbon. She fixes her soft gaze upon the spectator as she arranges a simple bouquet of flowers in her delicate hands.

Despite its charm, the portrait was deemed inappropriate and offensive by many due to the severe informality of a dress meant to be worn in the privacy of one’s boudoir. It was soon replaced by Marie-Antoinette à la rose, showing the queen in more traditional courtly attire.

In 1785, Vigée Le Brun was commissioned to paint a monumental portrait of the Queen. The portrait was to highlight the maternal characteristics of the Queen by having her appear with her three children. Marie-Antoinette et ses enfants (1787) shows a serene, benevolent Queen comfortably seated in a chair. Her feet rest upon a green cushion embroidered with golden arabesques. These same arabesques are mirrored in the multicolored Persian rug. Marie-Antoinette is clothed in red, stately, full-length gown with plunging décolleté edged in delicate white lace. Atop her simple coiffeur sits a stylish, red hat with white feathers and blue satin ribbon. Her outward gaze is confident, yet tranquil, as she loving embraces a restless baby on her lap, clothed in a white cap and gown with blue sash.

A blond-haired daughter with cherubic features, dressed in a similar velvet red gown with satin bows in blue and gold, lovingly gazes upward as she wraps her arms around her mother’s right arm. The third child is also elegantly clothed in a red velvet pant suit with white lace collar and blue satin sash. This piercing blue is reflected in every figure’s eyes. The child stands proudly next to a royal bassinet heavily draped in a deep, forest-green satin. The ensemble of voluminously-clothed figures is prominently arranged in a pyramidal form. This is in direct contrast to strong vertical lines created by the architectural columns and wooden cabinet situated in the background.

Due to the success of Marie-Antoinette en grand habit de cour, Vigée Le Brun was invited to paint a series portraits of the Queen. By varying the accessories, clothing, poses, and environment, the artist successfully highlighted certain inimitable characteristics of the Marie-Antoinette’s complex personality. This included her natural grace, elegance, and confidence. Vigée Le Brun’s portraits of the Queen also provided clear, invaluable insight into sociocultural norms which were visibly reflected in the representation of acceptable courtly attire.

Author: Jewel K. Goode

Jean-Honoré Fragonard: Inspiration for Karl Lagerfeld’s Chanel Haute Couture Spring 2017

Karl Lagerfeld’s Chanel Haute Couture 2017 collection, held in January 2017 at the Grand Palais in Paris, France, was a study in elegance, femininity, and sophistication. The line visibly referenced Le Colin-Maillard (1754-1756), or Blind Man’s Bluff, an eighteenth-century chef-d’oeuvre by French painter, Jean-Honoré Fragonard. Similar to Fragonard, who painted a variety of subjects including landscapes, genres, historical, grand interiors, portraits, mythological tales of Antiquity, Lagerfeld’s Haute Couture 2017 reflected the same level of diversity. The Chanel collection combined luxurious materials such as silk, satin, and chiffon. Long, lean silhouettes were created with cinched-in waists, high-waisted trousers, and gentle A-line skirts. The subdued color palette of cream, shades of pale pink and yellow, and beige were gently anchored with silver and gold accessories or ostentatiously highlighted with a profusion ruffles, feathers, paillettes, and embroidery.

Lagerfeld masterfully utilizes classic Chanel iconography primarily consisting of wool and tweed while cleverly implementing the same libertinage themes as Fragonard. The superfluous, licentious style was pervasive during the Enlightenment. Although viewed as blatantly hedonistic, romance, sensuality, and utopian pastoral scenes were artificially disguised as gallantry within the context of a modernized society. This ultimately created a complete fragmentation and detachment from its supposed sentiment. Le Colin-Maillard was Fragonard’s first foray into pastoral paintings. He utilizes a soft color palette including pink, blue, white, green, and yellow to evoke an erotically-charged, pastoral environment popular amongst the aristocracy. The scene evokes a lush, flowering pastoral scene framed by a soft blue sky. It is a flirtatious, sensual setting in which a young shepherdess wearing fashionable, rustic attire playfully peeks through the bandage covering her eyes, presumably placed there by her lover.

Lagerfeld borrows the elegant shepherdess of Fragonard’s Le Colin-Maillard and recontextualizes the figure as an haute-couture model. In both genres, she is the dominant, central figure. Positioned in a gentle contrapposto, the twenty-first century model and eighteenth-century shepherdess animate the scene/defilé with graceful, elegant movements. The voluminous fabric of Lily-Rose Depp’s pink, chiffon dress is illuminated by a soft, gentle light originating from above. Fragonard’s blond-haired heroine with undulating curls dons an unassuming straw hat tipped in pink, while those of Lagerfeld’s models sit atop sleek chignons.

Throughout the defilé, it is evident that Lagerfeld’s Chanel haute couture line is inspired by Le Colin-Maillard’s shepherdess juxtaposed with contemporary society. Her white, billowing, cotton sleeves mirror the whiteness of the eye bandage, as well as the undergarments covering her bosom. Delicate pink chiffon contrasts the grayish-blue silk undergarment extending to her ankles. This blue is mirrored in the shepherdess’s satin ribbon shoelaces. The delicate bunch of wildflowers tucked into her bosom, and the wispy ribbon which adorns her neck, encapsulate the romantic essence of Lagerfeld’s haute couture défilé.

The implementation of the chiaroscuro technique, strategically executed with mirrors and lights, provides strong visible juxtapositions between two distinct realms. A contrived, neoclassical/Art Déco sphere with glass pedestals and mirrored floors contrasts with romantic, luxurious colors, fabrics, and textures. The former being solid, weighted, and rigid; the latter being light, voluminous, and lush. This concept is evident with both Lagerfeld’s and Fragonard’s selection of materials, soft color palette, and positioning of architectural objects.

Similar to the painting, strong diagonals are formed during the défilé – created by light sources emanating from above. Vertical and horizontal divisions are distinct throughout Lagerfeld’s clever mise-en-scène which utilizes mirror refraction. Strong, architectural lines and obliques created by the glass pedestals and mirrored floors contrast the lushness created by the profusion ruffles, feathers, paillettes, and embroidery. Wildflowers, trees, ivy, and billowing fabric adorning Fragonard’s shepherdess create a utopian arrière-plan.

About Jean-Honoré Fragonard

Born in Grasse, Fragonard (1732-1806), or “Frago”, is one of the most influential painters of the eighteenth century, especially during the years preceding the French Revolution. Fragonard began his training as a painter with Jean-Baptiste Chardin and later with François Boucher. Soon thereafter, he was recipient of the Grand Prix award in 1752 which subsequently led to his acceptance into the Royal Academy of Painting in 1765. A series of important paintings were commissioned over the course of his lifetime including L’Aurore triumphant de la Nuit (1755), Le Verrou (1775), Le Jeu de la main chaude (1775), and Renaud entre dans la forêt (1761).

Author: Jewel K. Goode

Sources

Faroult, Guillaume. Album de l’exposition du Musée du Luxembourg. Fragonard amoureux: Galant et libertin. Réunion des musées nationaux – Grand Palais, 2015.

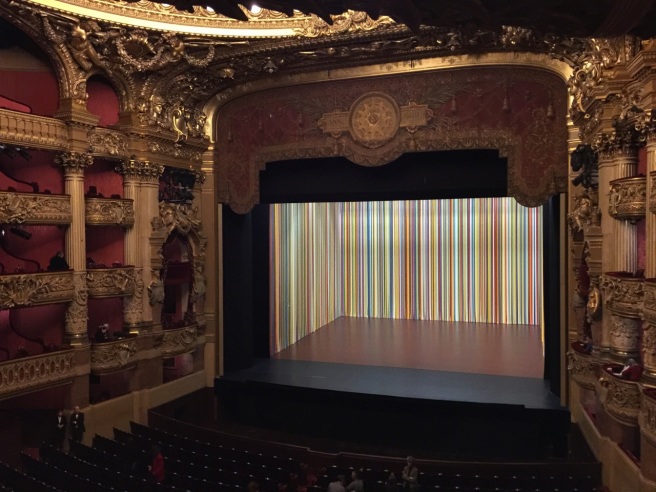

Karl Lagerfeld and the Opéra national de Paris: A multi-sensorial, artistic collaboration

The haute couture ballet costumes and set design for George Balanchine’s Brahms-Schönberg Quartet were created by Karl Lagerfeld for the Opéra national de Paris. Renowned dancers Bart Cook and Maria Calegari served as the choreographers, and I acted as the cultural liaison and assistant to choreographers, artists, and directors. The luxurious costumes reflect an innovative, collaborative approach to fashion in the rapidly evolving globalized community. Moreover, they fully activate the five senses while providing elements of fantasy of a bygone era. For, “There will never be a world without fantasy, which expresses the unconscious unfulfilled” (S. Kaiser, 1997).

This is an essential point, since art, fashion, and culture inhabit the same multi-sensorial landscape. They represent a constantly evolving visual language which must be effectively transmitted to spectators. Inaugurated in 1875, the OnP formerly represented an elitist Parisian society. The institution was historically linked to utopian images of wealth, power, prestige, and elegance. Therefore, Lagerfeld’s costume designs for each of Balanchine’s four acts needed to the encapsulate the Zeitgeit of the OnP. That essence was effectively transmitted through a consistent visual theme involving textures, costume accessories, and classical ballet silhouettes. A muted color palette of white, pale pink, and crème-orange created a bold visual juxtaposition with the monochromatic interjection of black and white details and piping. Traditionally feminine elements and curvilinear shapes were visible with velvet headpieces and armbands, satin ribbons, tulle/chiffon tutus, and bejeweled caps. These contrasted the straight lines and geometrical shapes traditionally considered masculine.

Lagerfeld conceptualized various sketches which were inspired by the Vienna Secession, an artistic movement established in 1897. Costumes were skillfully constructed in the OnP couture atelier according to Lagerfeld’s initial artistic intentions, but still allowed for subsequent modifications and adjustments of material, fabric, and accessories. Thus, costumes were individually adapted to each ballet dancer, taking into consideration rigorous choreographic maneuvers. They also accounted for other variables including lighting, sound, and stage conditions. This resulted in the creation of regal, yet fashionable costumes which contributed to the multi-sensorial landscape while integrating an advanced degree of technological innovation and functionality.

Lagerfeld’s extensive research resulted in the creation of tailored men’s black and white suede waistcoats, as well as folklore-inspired, embroidered headdresses. The women’s costumes included black and white bodices with princess seams in satin and velvet attached to voluminous tutus constructed of pink, orange, and white tulle/chiffon. Use of luxurious fabrics and detailed embroidery created a sophisticated, glamorous environment of classic, understated elegance. It also alluded to a previous era where clothing was symbolic of an individual’s social status and morality – whether actual or contrived. Lagerfeld’s set design purposefully evoked an ancient palace adorned with heavy, gray, floor-length drapery. This contrasted the color palette and texture of the costumes. Such an atmosphere was meant to reference the waning splendor of the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

Artistic collaborations between the French heritage institution and fashion have steadily increased in the globalized economy. The OnP has hosted a variety of cultural events and fashion shows such as Stella McCartney and Dries van Noten. Moreover, the OnP has collaborated with renowned fashion designers including Christian Lacroix for George Balanchine’s Le Palais de cristal, and Yves Saint-Laurent for Roland Petit’s Notre-Dame de Paris. Recently, it has begun collaborative efforts with contemporary, avant-garde fashion designers such as Iris van Herpen for Benjamin Millepied’s Clear, Loud, Bright, Forward, Alessandro Sartori for Millepied’s La nuit s’achève, and Mary Katranzou for Justin Peck’s Entre chien et loup.

Paris, France: Opéra national de Paris, Palais Garnier

Paris, France: Opéra national de Paris, Palais Garnier

Maison Schiaparelli: A History and Revival

Elsa Schiaparelli (1890-1973) was born into an aristocratic and intellectual family at the Palazzo Corsini in Rome, Italy. The Italian-born French couturière is best known for the quality and originality of her work infused with vibrant colors, intricate embroidery, architectural elements, bold prints, and pronounced textures. Yves Saint Laurent once commented on Schiaparelli’s profound success as an Italian in Paris: “Elle a gifflé Paris, elle l’a ensorcelé, et en retour Paris est tombé amoureux d’elle” (Baxter-Wright, p. 27). She brought an Italian sensibility to French haute-couture with cleverness, whimsy, femininity, and expertise. In addition, artistic collaboration with others allowed Schiaparelli to skillfully implement innovative techniques, materials, and various genres into her idiosyncratic designs.

Schiaparelli was oftentimes regarded as an artist as much as a designer. Gabrielle (Coco) Chanel’s statement reflects this sense of artistry, “… cette artiste italienne qui fait des vêtements (Baxter-Wright, p. 71). Schiaparelli soon caught the attention of renowned fashion design Paul Poiret, as well as Gabrielle Picabia, wife of Dadaist painter Francis Picabia. Her early work produced at the atelier in rue de l’Université consisted of geometrical designs and was considerably more conservative than later years. By 1927, Schiaparelli was catapulted to success with the creation of a hand-knit sweater with a black and white trompe l’oeil motif. It was immediately deemed an “artistic masterpiece” by Vogue and launched her career. This eventually led to the opening of her atelier on 4, rue de la Paix, “Schiaparelli – Pour le Sport” with designs seamlessly blending haute-couture and sportswear.

Schiaparelli’s spirit of entrepreneurialship and business acumen were apparent very early, as she surrounded herself with creative talents including: Meret Oppenheimer, Alberto Giacometti, Lesage, Jean Schlumberger, Lina Baretti, Jean-Michel Frank, Roger Vivier, and Marcel Vertès, among many others. Schiaparelli was the first woman to be featured on the cover of Time magazine in 1934. This marked the beginning of Schiaparelli’s experimentation with jewelry design, various motifs, aerodynamic cuts, intricate embroidery, bold colors, and innovative materials such as Swarowsky crystals, rhodophane, and crushed rayon crepe. Rhodophane is a transparent and fragile material which appears like glass, while crushed rayon crepe resembles tree bark. Her fragrance “S” was launched in 1928. Soon thereafter, a collection of three perfumes, Souci, Salut, and Schiap, was created in 1934. Schiaparelli’s designs attracted strong, independent women, as well as famous customers such as Katherine Hepburn, Marlene Dietrich, Greta Garbo, Lauren Bacall, Vivien Leigh, and Wallis Simpson, the future Duchess of Windsor. Her designs were lauded for celebrating, not neglecting, the feminine form with nipped-in tops, bold lines, and skirts to flatter the real woman. Schiaparelli once commented, “Il ne faut pas adapter le vêtement au corps, mais faire en sorte que le corps s’adapte au vêtement” (Baxter-Wright, p. 89). In 1932, the Couture House was known as “Schiaparelli – Pour le Sport, Pour le Ville, Pour le Soir”, and later moved into its current location Hôtel de Fontpertuis at 21 place Vendôme in 1935.

Schiaparelli was continually inspired by illustrations, architecture, fantasy, the Italian Commedia dell’Arte, and the theatricality of Surrealism. During this period, she often collaborated with artists. She and Salvador Dalì created several controversial pieces, including “Squelette” (Skeleton Dress, 1938), and “Homard” (Lobster Dress, 1937), a recurrent theme in Dalì’s work which often had sexual connotations. It features a large, blood-red lobster motif on a simple, white dress, strategically located between the thighs. “Larmes” (Tears Dress, 1938) is part of the “Cirque” collection inspired by Dalì’s “Trois jeunes femmes surréalistes tenant dans leurs bras les peaux d’un orchestra” (1936). Designed just before the outbreak of World War II, the silk crêpe dress was created as a “mourning dress”, accompanied by a long veil and tears in a trompe l’oeil motif. Schiaparelli states, “Quand les temps sont difficile, la mode est toujours outrancières” (Baxter-Wright, p. 79). Other notable collaborations were with Jean Cocteau, whose drawings were featured on many of her designs, René Magritte (for the fragrance bottle inspired by his “Ceci n’est pas une pipe” painting), and Man Ray throughout the 1930’s and 1940’s.

Schiaparelli was able to skillfully translate the utopian, dreamlike state of Surrealist imagery into her innovative designs, and was the first to give her collections a theme. Some of the clothes from this period included, “Stop, Look, and Listen” (1935), “Paris in 1937” (1937), and “Music” (1937). “Zodiac”, “Pagan”, and “Circus” were all created in 1938, and “Commedia dell’Arte” was created shortly thereafter (1939). Schiaparelli also served as costume designer for various Hollywood films including “Every Day’s a Holiday” (1937) and “Moulin Rouge” (1952). Much of her success was due to an ability to conceptualize and execute a broad range of items including bathing suits, sportswear such as the jupe-culotte, evening gowns, wrap dresses, hats, jewelry, and perfume.

Perhaps most significant was the creation of her Shocking perfume and “shocking pink” trademark color in 1937. Commenting on the color, Schiaparelli once stated: “Une couleur qui donne la vie, la couleur de toute la lumière du monde, de tous les oiseaux et de tous les poisons du monde réunis, une couleur de la Chine de du Pérou, mais pas de l’Occident » Baxter-Wright, p. 48). The perfume bottle was designed by Leonor Fini, and represented a dressmaker mannequin referencing the physique of Mae West decorated with porcelain flowers and a velvet measuring tape. The Maison Schiaparelli proved to be an international success, and Elsa became the first European to receive the Nieman Marcus Award for services to fashion in 1940. However, this marked a period of decline for the House of Schiaparelli, and it was forced to close in 1954, the same year her autobiography, Shocking Life, was released.

Nearly fifty years later, the Schiaparelli archives and rights were acquired by Diego della Valle in 2006. Subsequently, the Maison Schiaparelli reopened at stately Hôtel Fontpertuis on 21, place Vendôme in 2012. As a tribute to the original founder, Christian Lacroix designed an haute-couture collection one year later. Soon thereafter, Farida Khelfa was appointed Ambassador, and Marco Zanini was appointed creative director in 2013. In January 2014, the Maison Schiaparelli successfully presented its first haute-couture show at Hôtel Fontpertuis since its 1954 closing. By re-contextualizing and reconfiguring particular elements, Zanini was able to capture the essence of Maison Schiaparelli – transforming it into a contemporary, yet timeless, brand with Italian-Parisian sensibilities. The Théâtre d’Elsa references 1930’s Parisian theatres. It is a chic, cosmopolitan realm encapsulated in elegance, splendor, and glory.

Designs consisting of bold, masculine silhouettes, tweeds, and tartans draped over full, opulent gowns made of shimmering rhodophane creates a sense of restrained elegance. However, there is also a strategic use of vibrant, saturated colors, and well as the trademark “shocking pink”. Flowing, luxurious fabrics, and the appearance of hand-painted prints on silk chiffon and organdy point to the complexity and detail of the couturière method. These pieces are carefully juxtaposed with structured capes with strong shoulders, bold, architectural shapes, and intricate embroidery reminiscent of Spanish boleros. Complex details and embroidery appearing on the back add another dimension to the idiosyncratic creations. Sparkling, oversized brooches consisting of pierced hearts, irises, suns, stars, padlocks, and the ES initials illuminate each colorful ensemble. The totality of the Fall/Winter 2015-2016 collection reflects a masterful re-interpretation and re-contextualization of Elsa Schiaparelli’s twentieth century designs by Marco Zanini.

Author: Jewel K. Goode, Independent Curator, Photographer, and Educator

contact: jewelkismet@gmail.com

Sources:

Bater-Wright, Anne. Schiaparelli. Groupe Eyrolles, Paris. 2012.

Schiaparelli: Paris website. N.d. 2 November 2015.

The exhibition Fragonard amoureux: Galant et libertin (Fragonard in Love: Suitor and Libertine) is currently located at the Musée du Luxembourg from September 16, 2015 until January 24, 2016. Born in Grasse, Jean-Honoré Fragonard (1732-1806), or « Frago », is thought to be one of the most influential painters of the 18th century, especially during the years preceding the French Revolution. From 1748-1752 Fragonard began his training as a painter with Jean-Baptiste Chardin and François Boucher. Soon thereafter, he was the recipient of the Grand Prix award in 1752, which subsequently led to his acceptance into the French Royal Academy of Painting in 1765. A series of important paintings were commissioned over the course of his lifetime including L’Aurore triumphant de la Nuit (1755), Le Verrou (1775), Le Jeu de la main chaude (1775), and Renaud entre dans la forêt (1761). The Enlightenment encouraged variations on the romantic genre, directly translated into painting or other artistic forms. Although Fragonard unabashedly indulged in the themes of romance and love, he also painted a variety of subjects including landscapes, genres, historical, grand interiors, and portraits.

A direct vestige of the Grand Siècle, the concept of galenterie was representative of French national identity in the 18th century, evoking utopian pastoral scenes. L’amour galant encouraged tenderness, sincerity, mutual respect, and loyalty. As a student of François Boucher (1703-1770), Fragonard was directly influenced by the former’s invention of an iconography that was a combination of love, romance, and pastoral gallantry. The ability to appropriately express emotions and sensuality was a major concern of artistic, literary, and philosophical circles. François Boucher’s Les Charmes de la vie champêtre (1735-1740), also visible at the exhibition, was inspired by Hubert-François Gravelot’s illustrations for the literary work, L’Astrée (1733) written by Honoré d’Urfé (1567 – 1625).

The exhibition opens with the theme of Le berger galant (The Gallant Shepherd) which includes Le Colin-Maillard (1754-1756). It was Fragonard’s first foray into pastoral paintings, and it clearly borrowed essential formal elements from Boucher including clothing, disposition, lighting, and color palette. Le Colin-Maillard (Blind Man’s Bluff) evokes a lush, flowering pastoral scene framed by a soft blue sky. It is a flirtatious, sensual scene in which a young shepherdess in fashionable, rustic attire playfully peeks through the bandage covering her eyes, presumably placed there by her lover. He has light-brown curly hair, and is clothed in a yellowish-green overcoat with pink shirt. The young boy is in ¾ view, positioned slightly behind the shepherdess’s right shoulder, and is attempting to tickle her with a string.

The elegant shepherdess is the dominant, central figure, positioned in a slight contrapposto which animates the entire scene with movement. The voluminous fabric of her pink, satin dress is illuminated by a soft, gentle light originating from the upper left corner of the painting. A yellowish, straw hat tipped in pink sits atop waves of undulating, blond hair. White, billowing, cotton sleeves reaching her elbows mirror the whiteness of the eye bandage, as well as undergarments covering her bosom. The pink fabric contrasts the grayish-blue silk undergarment which extends to her ankles. This blue is mirrored in the ribbons of the shepherdess’s shoelaces, the delicate bunch of wildflowers tucked into her bosom, and the wispy ribbon which adorns her neck.

Fragonard utilizes a soft color palette including pink, blue, white, green, and yellow to evoke an erotically-charged, pastoral environment popular amongst the 18th century aristocracy. Other elements include the appearance of two, playful putti which serve as artistic inspiration. One is positioned on his back at the shepherdess’s feet, engaging in a game of stick and string with the blindfolded girl, while the other is positioned in the far left of the painting. He is partially hidden by the lush, sprawling foliage which covers deteriorating architectural elements prominently located in the foreground (stairs, vase, and base), as well as the background.

Clever groupings of figures, a skillful implementation of the chiaroscuro technique, and the decay of solid, structural features provide strong visible juxtapositions between two distinct realms: a contrived, neoclassical construction, and a utopian pastoral, Arcadia. The former being solid, weighted, and rigid; the latter being light, voluminous, and lush. This concept is also evident with Fragonard’s selection of materials, soft color palette, and positioning of roughly-textured wooden objects in the foreground (lower right-hand side of the painting). They are also located immediately to the left of the shepherd and shepherdess. A strong diagonal is formed across the painting which is created by the light source emanating from the upper left corner. Vertical and horizontal divisions are distinct throughout the pastoral scene. Strong, architectural lines of the stairs, background stone structure, pedestals, and obliques contrast the lushness provided by sprawling wildflowers, trees, ivy, and billowing fabric adorning the two central figures and playful putti.

The choice of paintings, engravings, and drawings in the Musée du Luxembourg’s current exhibition are carefully positioned according to specific themes. These mirror the trajectory of Fragonard’s artistic production from the beginning of his career until his death in Paris on August 22, 1806. The first of these divisions is Le berger galant (The Gallant Shepherd). It is the opening theme of the current exhibition. Following is Les amours des dieux (The Loves of the Gods), which reveals mythological tales of Antiquity. Said to have been executed in a superfluous, licentious style of painting, this « libertinage » theme was a favorite topic amongst the élite. Critiques argued that it was a theme disguised as gallantry, and it was, in fact, blatantly hedonistic. This created a complete fragmentation and detachment from its supposedly romantic sentiment.

Next, Éros rustique et populaire (Rustic and Popular Eros), was a theme which inspired Fragonard after his first trip to Rome in 1756. This encouraged two distinct styles. The first referenced the popular literary genre poissard. Artistic production pointed to carnal urges and pictorial references of rustic scenes of 17th century Flemish painters such as Rubens (1577-1640). The second style referenced Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s (1712-1778) love of nature. Other themes worth exploring in the exhibition include: Fragonard illustrateur de contes libertins (Fragonard, Illustrator of Libertine Tales), Pierre-Antoine Baudouin, un maître en libertinage (Pierre-Antoine Baudouin, A Liberinist Master), Fragonard et l’imagerie licencieuse (Fragonard and Licentious Imagery), La lecture dangereuse (Dangerous Reading), Le Renouveau de la fête galante (The Revival of the Fête Galante), L’amour moralisé (Love Moralized), La passion héroïque (Heroic Passion), and Les allégories amoureuses (Romantic Allegory).

Author: Jewel K. Goode, Independent Curator, Photographer, and Educator

contact: jewelkismet@gmail.com

Sources

Faroult, Guillaume. Album de l’exposition du Musée du Luxembourg. Fragonard amoureux: Galant et libertin. Réunion des musées nationaux – Grand Palais, 2015.

Newsletter N.2, Fall Edition 2015

I am very pleased to announce the publication of Newsletter N.2, Fall Edition 2015. Since arriving in Paris, I have been continually inspired by the city’s beauty, elegance, and charm. Long strolls along the Seine, through medieval cobblestone streets, and down the stately Champs-Élysées, have left me breathless. The Paris Reflections blog series serves as an autobiographical and photographic journey through the City of Light. Currently available editions: N.1: Palais-Royal, Comédie-Française, and the Pyramide du Louvre, N.2: Domaine de Chantilly and exhibition at Musée Condé, “Le Siècle de François 1er,” N.3: Sainte-Chapelle, Palais de la Cité, and N.4: Musée de Cluny.

The purpose of the Paris Reflections blog series is to inform you of current activities, events, and exhibitions in the art world. It is my hope that they will be the impetus to initiate provocative discussions, encourage thoughtful expression, stimulate creativity, and provide invaluable learning experiences for the globalized community. Art should be the embodiment of many things, and it is necessarily subjective. Each individual has a unique perspective of the world which affects their particular viewing experience. Emphasizing the socio-cultural, historical, and political significance of various artistic traditions will help to promote a deeper understanding of art, photography, architecture, design, and fashion.

Future Newsletters will be accompanied by relevant links to photographic essays, brief informational texts, and critiques. This is essential, since active participation in extensive research and art analyses are both necessary components for effective curatorial procedure. Interviews with art world professionals including museum directors, curators, gallery owners, and independent artists will be conducted, when possible. In addition, customized gifts, calendars, and other products will be available in the near future.

Lastly, I am pleased to announce that the 2015 publication of my PARIS photo book is now available for purchase. It is a visually compelling collection of powerful photographic essays, and provides a romantic journey through the streets of Paris. The book is delightfully composed of beautiful, vibrant images of people, pastries, monuments, and daily life. Find it on the following sites: Blurb hardback and e-book editions, Amazon, and in the Apple iBookstore.

Jewel Kismet Designs continues to flourish, thanks to increased visibility through various social media outlets such as Facebook and Twitter. Thoroughly embracing these innovative approaches allows art to be discovered from a fresh, modern perspective. It is my hope that active engagement with an international audience not only increases visual arts access to the general public, but also enriches the lives of the globalized community.

Thank you for your support.

Sincerely,

Jewel K. Goode, Independent Curator, Photographer, and Educator

contact: jewelkismet@gmail.com

Paris Reflections, Fall Edition N.4: Musée de Cluny

The Musée national du Moyen Âge, or Musée de Cluny, is located in the Hôtel de Cluny. The first establishment was constructed by Pierre de Chaslus after the acquisition of the ancient baths by the Cluniac Monastic Order in 1340. The selection of artifacts masterfully reflects the historical and metaphysical transformation of France. The weighted sense of socio-political, religious, and cultural obligations are complemented by the solemnity and relative darkness of the majority of the exhibition spaces. The wealth of artistic production including illuminated manuscripts, shields of armor, intricately woven tapestries, vibrantly stained-glass windows, reliquaries, and sculpture are all intimately bound to the Hexagone’s complex history involving war, conflict, religion, trade, society, and culture.

The Lady and the Unicorn tapestries (c. 1500) from the Château de Boissac were acquired in 1882, and are an example, par excellence, of medieval artistic production. The ensemble is comprised of a series of six wool and silk tapestries which reflect the beauty and charm of the mythical unicorn. Five of the six panels feature a representation of the five senses. However, the sixth panel, entitled “To My Only Desire,” is thought to evoke the sixth sense – the spiritual and moral center. The coat of arms with three crescents belongs to the Le Visite family. Although the subject is different in each, the content remains the same. Each tapestry has a deep pink background filled with delicately sprawling flowers, abundant fruit trees, and various animals including rabbits, goats, monkeys, and lions. The activity between the Lady, the unicorns, and the animals always remains in the center of the tapestry, anchored by a lush green, oval zone.

The present town house was constructed during the second half of the 15th century. It was completed during the first half of the 16th century by the Jacques d’Amboise abbacy and follows a temporal construction: baths, medieval town house, and Couvent des Mathurins. Due to the unique implementation of the ancient Roman technique known as opus vittatum mixtum, the Hôtel de Cluny remains architecturally sound. Subsequent restoration and modifications were undertaken by Albert Lenoir (1801-1891) in the 19th century in order to help preserve the establishment. He had presented a project to create a historical museum that united the Palais des Thermes and the Hôtel de Cluny in 1832, with collections displayed in the buildings that housed them: antiquity in the frigidarium, Middle Ages in the Hôtel de Cluny, and subsequent periods in buildings adjacent to the Couvent des Mathurins. However, the destruction of these buildings in 1860 prevented the project from being realized.

The Musée de Cluny was conceived in the 19th century by Alexandre du Sommerard (1779-1842), magistrate at the Cour des Comptes (Court of Audit) and passionate art collector. At the end of his life, he had amassed an inventory of 1,434 objects. In 1834 he mused, “In 1832 the imagination of an art lover, who had long collected objets d’art from eras corresponding to that of the construction of the town house, gave him the idea of enhancing his collection with the harmony of the setting,” (Musée du Cluny: A Guide, p. 11). The Musée de Cluny opened in 1844 under the supervision of the Commission des Monuments Historiques with Alexandre du Sommerard’s son, Edmond, acting as its first director.

During his directorship, Edmond Sommerard made significant acquisitions, including the Lady and the Unicorn Tapestries (c. 1500), the Golden Rose (1330) by Sienese goldsmith Minucchio da Siena, the religious twenty-three scene Tapestry of Saint Stephen (c. 1500) which recounts the life of Saint Stephen and the movement of his relics from Jerusalem to Constantinople; and the hanging votive Guarrazar Crowns from Visigoth Spain (7th century). He also wrote the first museum catalogue which was successfully published and redistributed several times. Presently, the museum houses a vast collection of pieces spanning the ages: Antiquity, Romanesque art, Limoges work, Gothic art, and art from 15th century can all be found in the archives of the current establishment. However, due to the physical limitations of space, the Museum has had to reconfigure and re-conceptualize its collection. After World War II, Francis Salet and Pierre Valet limited its displays to thematically organized medieval works of art.

Author: Jewel K. Goode, Independent Curator, Photographer, and Educator

contact: jewelkismet@gmail.com

Sources: Musée du Cluny, Musée national du Moyen Âge: A Guide. Éditions de la Réunion des musées nationaux, Paris (2009).